March 11, 2022

Last summer, Renaissance released Trip Steps for Mathematics, which are essential math skills that are also disproportionately difficult for students to learn at grade level. You’ll find detailed information about math Trip Steps, including how we identified them and how you might use them when planning instruction, in this blog from last fall.

At the request of our school and district partners, we’re now releasing Trip Steps for Reading, which span kindergarten through grade 12. We recently had the opportunity to discuss reading Trip Steps with three of our Renaissance colleagues: Dr. Gene Kerns, Vice President and Chief Academic Officer; Julianne Robar, Director, Metadata and Product Interoperability; and Dr. Jan Bryan, Vice President and National Education Officer.

Highlights from our conversation appear below.

Why does Renaissance use the name “Trip Steps” to describe these disproportionately difficult reading and math skills?

Gene Kerns: One of my more memorable experiences as an educator was chaperoning a high school trip to Europe. We visited several medieval castles, and we learned that the staircases deliberately had steps of different heights. People living in the castle would obviously be familiar with this, and would know that the fifth step or the eighth step was taller than the others. Invaders, however, wouldn’t know about these “trip steps,” and would be more likely to trip and fall when trying to storm the castle.

In education, we often describe learning as a staircase, with each skill being slightly more difficult than the one that comes before it. This is generally accurate, but as students progress within and across grade levels, they occasionally encounter a skill that is significantly more difficult than the prior skill, and which may cause a stumble in learning. The concept of “trip steps” immediately came to mind here, to provide a visual representation of this.

Why did Renaissance decide to release lists of Trip Steps now?

Gene Kerns: When the COVID-19 pandemic forced schools to switch from in-person to online learning, educators needed a quick and reliable way to prioritize essential skills, so they could make the best use of limited instructional time. To help, Renaissance made our Focus Skills freely available to every school and district. Focus Skills are the essential reading and math skills at each grade level, based on each state’s standards of learning. They are also important prerequisites for future learning—the skills that students must master in order to progress.

Now that we’ve lived through two years of the pandemic, educators are, in a sense, ready to take the next step. While all Focus Skills are essential, some of them are demonstrably more difficult for students to learn than others. These are the Trip Steps. Knowing which reading and math skills are most difficult for students to learn at grade level is valuable information to have as you’re planning instruction. Trip Steps also support the important work of learning recovery, by helping educators to identify essential yet challenging skills from prior grades that students may have missed out on due to the disruptions.

What major differences do you see between reading and math Trip Steps?

Julianne Robar: With Trip Steps for Mathematics, we generally see a fairly tight grade range for each domain. For example, in grades 1–4, we see multiple Trip Steps in Whole Number Concepts and Whole Number Operations. As students move into middle and high school, they’re then applying these skills to new domains—particularly Geometry and Algebra, where they need these skills to find area or solve multi-step problems.

With Trip Steps for Reading, we tend to see a larger grade span within each skill area. For example, the Trip Steps for Character and Plot span grades K–8, the Trip Steps for Main Idea and Details span grades 2–10, etc. In the document’s introduction, we highlight Author’s Purpose and Perspective, which has Trip Steps spread across grades 2, 7, and 10. Looking at the list, it’s clear how these skills build on one another and

Gene Kerns: The writer Stephen Pinker describes math as “ruthlessly cumulative”—a phrase we’ve quoted often when speaking about math Trip Steps and how these skills build on each other. This description also applies to reading Trip Steps, but in a somewhat different way. What sets reading apart is how students must operationalize the skills they’ve learned through all the different genres they encounter. Reading a novel is different from reading a poem, an essay, a persuasive piece, or a newspaper article.

I’m reminded of the saying, “Nobody cares for figurative language in a technical manual.” The Trip Steps in the Conventions and Range of Reading skill area highlight this important difference between reading literary texts and informational texts. This begins in grade 1 with the Trip Step, Understand the general differences among various print and digital materials (e.g., storybooks, fairy tales, informational books, newspapers, websites).

What strikes you in looking at the Trip Steps for Reading in grades K–3? Any surprises?

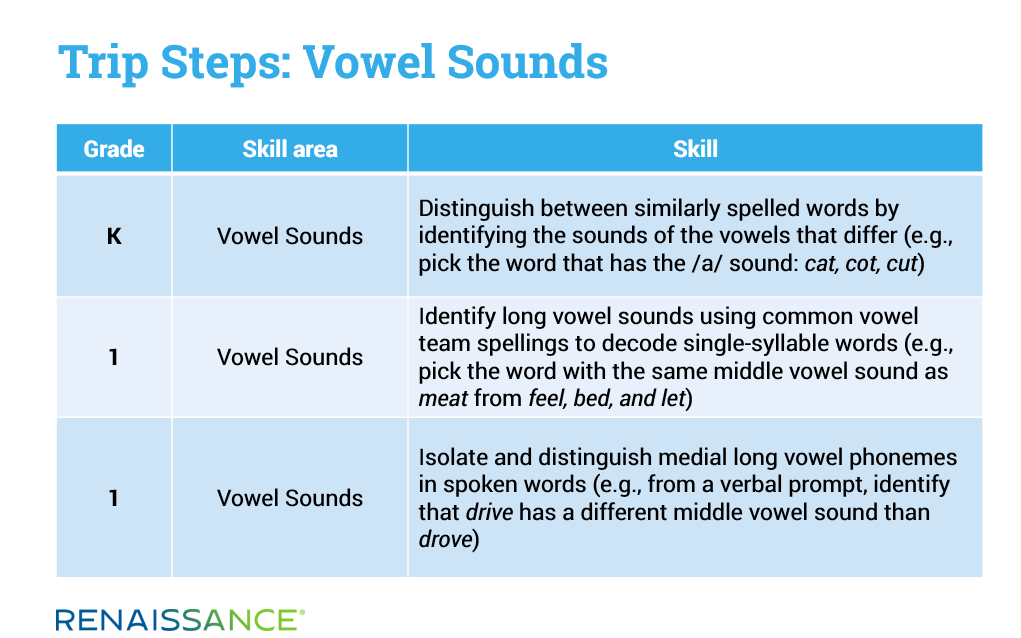

Jan Bryan: In most states, grade 1 has the highest number of reading Focus Skills, so I’m not surprised to see the large number of reading Trip Steps in kindergarten and grade 1. We know that students are building important foundational skills at these grade levels, particularly for decoding. The skill areas we see here—Phonemes, Vowel Sounds, and Consonants, Blends, Digraphs—will align with educators’ expectations.

What does strike me is the difficulty of some of these Trip Steps. For example, consider the kindergarten Trip Step for Vowel Sounds: Distinguish between similarly spelled words by identifying the sounds of the vowels that differ (e.g., pick the word that has the /a/ sound: cat, cot, cut.) Using the empirical difficulty data from our Star Assessments, we can see that this skill is roughly two grade levels ahead of kindergarten. This may lead someone to ask, “Then why isn’t this skill taught in second grade instead?” The answer is that it’s a prerequisite for the skills that come next. Even though it’s a difficult skill for kindergarteners to learn, it’s essential to their progression—which is the very definition of a Trip Step.

Gene Kerns: This example reminds me of the importance of beginning with phonemic awareness. Without training, the human mind perceives words as wholes, not as phonemes: “cat” rather than /k/ /æ/ /t/. As adults, we often forget how difficult phonemic awareness is for young children, in the sense that we’re asking them to slow language down and isolate individual sounds—hardly a natural act. We do this because once children learn the parts, they can put them back together again in order to get meaning from the written word, which is absolutely essential for literacy development.

To return to the question of surprises, some people may be surprised to only see one reading Trip Step for grade 3. Given the many state policies around grade 3 reading, this may be puzzling at first. It’s important to remember, though, that states’ high-stakes grade 3 tests are meant to assess students’ reading development through grade 3, not just in grade 3. This includes all of the critical decoding skills in kindergarten and grade 1 that Jan just mentioned.

What strikes you in looking at the Trip Steps for Reading in grades 4–12? Were you surprised to see that grade 7 has more reading Trip Steps than any other grade?

Jan Bryan: We jokingly said that if you see a seventh grader, wish them well, and if you see a seventh grade teacher, take them out to dinner!

On a more serious note, when you look at the grade 7 Trip Steps, you’ll see that we’re almost asking students to be mind readers. The skill areas deal with author’s purpose, author’s word choice, connotation, cause and effect, etc., and the skills begin with words like “Interpret,” “Analyze,” “Explain,” and “Draw conclusions.” This is not something that comes naturally to many 12- and 13-year-olds. I can imagine a seventh grade teacher asking, “What does the author mean here?”, and a student replying, “I don’t know, let me call him and ask him…”

Gene Kerns: When I was a district administrator, we used the phrase “reading the lines” to describe literacy skills in the early grades. In other words, students can generally answer the teacher’s questions by pointing to specific words or sentences in a text. You can see multiple examples of this in the list of Trip Steps, such as identifying short and long vowels in grade 1, locating key details in an informational text in grade 2, and providing the sequence of events in a text in grade 3. In all of these cases, students can literally put their fingers on the answer in the text.

When students move into middle and high school, they’re suddenly asked to read between the lines, as Jan points out. They’re making inferences, analyzing figurative language, evaluating arguments and evidence, and drawing conclusions. This is a massive shift in complexity and in how students interact with texts. We see the beginnings of this in late elementary and middle school, but it increases exponentially in grades 7 and 8.

Julianne Robar: In this sense, Trip Steps align with Webb’s Depth of Knowledge. In the lower grades, we see a lot of “Identify…” and “Distinguish…” In the later grades, the emphasis shifts to “Explain…,” “Compare…,” and “Analyze…,” which have a greater cognitive demand.

Jan Bryan: It’s often said that in grades K–3, students are learning to read, while in grades 4–12, they’re then reading to learn. This is a useful shorthand, and it’s true that once students have learned the mechanics of reading, daily independent reading is essential for building background knowledge and vocabulary, and for developing the stamina to read the long and complex informational texts they’ll encounter in college and career. However, the Trip Steps for middle and high school highlight the equally important role of teacher-led instructional reading practice in helping students to learn these challenging and more abstract skills.

How might teachers and administrators use Trip Steps for Reading this spring and beyond?

Jan Bryan: The guidance in our earlier blog on math Trip Steps is equally relevant to reading. We suggest that grade-level teams plan instruction and share resources. A focus on prerequisite skills and student motivation, along with frequent checks for understanding, are also part of our recommendations.

Gene Kerns: If I were an administrator right now, I’d devote my data team meetings to discussing Focus Skills. Yes, I realize that teachers must also cover non-Focus Skills this year, but—given the limited time and the amount of ground that needs to be made up—I’d put the emphasis on the essentials. Trip Steps then provide another tool for prioritization, a way to “zoom in” on the Focus Skills that will likely require the most instructional time, the most support, and the most student practice.

I’d also share the list of Trip Steps with my master teachers and instructional specialists. I’d ask them to find quality resources, lesson plans, manipulatives, activities—in short, any instructional tools that would give my teachers the best shot at teaching these skills that are both absolutely necessary and really challenging for kids to learn.

For more insights on instructional reading practice, check out the book Literacy Reframed, written by Gene Kerns, Jan Bryan, and others. You can order a copy from your favorite bookseller or directly from the publisher.