June 18, 2021

In a recent blog, we explored the impact of COVID-19 school closures on preschool- and kindergarten-aged children. In this blog, we’ll continue the conversation by focusing specifically on preschool and pre-K programs—and on how teachers and administrators can best address children’s needs and accelerate learning in the new school year.

We discussed these topics with Dr. Scott McConnell, Director of Assessment Innovation at Renaissance and Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of Minnesota, and Dr. Alisha Wackerle-Hollman, Assistant Research Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of Minnesota. We were joined by Dr. Jan Bryan, Vice President and National Education Officer at Renaissance, and Heidi Lund, Senior Product Manager at Renaissance.

Terminology

Q: Let’s start with terminology. Can “preschool” and “pre-K” be used interchangeably? Or do these refer to different types of programming?

Scott McConnell: There are a lot of service delivery models for children before they enter kindergarten. In the past, we used a variety of terms for slightly different experiences: nursery school, childcare, daycare, preschool, Head Start, etc. Now, it’s more common to talk about preschool, pre-K, or early education. There are still slight variations across programs, but they’re all resources for helping children to develop socially and academically.

This change in terminology happened over several decades, as federal and state governments blurred the lines between traditional daycare and early childhood education. Advocates and policymakers recognized that many children—especially those in high-risk groups, such as children living in poverty and children with disabilities—were spending hours in daycare, which presented an opportunity to make better use of this time for children’s development.

We’ve also recognized that what happens to kids before they enter kindergarten is an important contributor to how well they do in K–12 education. That’s why we’ve directed more attention and resources to these programs, and why states have implemented formal processes—such as targeted and universal pre-K, Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRIS), and a variety of practice innovations—to provide stronger supports for early learners.

Alisha Wackerle-Hollman: I think “quality” is the key term here. I worry less about the differences among programs and more about the quality of what’s happening in each of those spaces. The level of services and support they’re providing to children in key domains—language, literacy, numeracy, and social-emotional development—is far more important than the label each program uses.

Kindergarten readiness

Q: Is it accurate to say that “kindergarten readiness” is the goal of preschool programs? Or is this a misunderstanding?

Scott McConnell: In some states, school isn’t compulsory until children are 7 or 8, but there’s still a fairly common cultural expectation that children will be enrolled in kindergarten when they turn 5. What happens before this is generally not compulsory, however, and kindergarten teachers accordingly expect a wide variation in the skills and capabilities of the children who arrive in their classrooms each year. Some children will have received a lot of resources and attention from parents and from preschool programs, while others won’t have received these things.

Contrast this with, say, high school graduation requirements. In the case of high school seniors, we can say that school districts have had these kids for 13 years, so there is a certain degree of accountability we can assign to the district, the schools, the teachers, the parents, and the students. We’re saying: Here’s the content we expect you to learn, and we’re going to provide instruction and resources and support for this. It seems reasonable to have expectations after 13 years.

But when children arrive for kindergarten, we can’t make this argument. We haven’t necessarily given them any specific supports, so talking about “readiness requirements” doesn’t make a lot of sense. Granted, we know that foundational skills in language, literacy, and numeracy are predictive of later success, so it’s important to encourage and support children’s development in these domains. In some places, you’ll find a tighter alignment—such as in pre-K programs that are run by districts, with the expectation that kids will then enroll in kindergarten in the district. This provides an opportunity to align what we expect of the children, and the resources we provide to them, so that when they enter kindergarten, they have skills that fit well with that environment.

We see similar effects when public and private programs work toward common goals. Again, we’re aligning our supports and expectations for preschool students with the expectations and instruction we will provide to them in the primary grades.

Alisha Wackerle-Hollman: States have established different early learning standards. Here in Minnesota, we have the Early Childhood Indicators of Progress (ECIPs), for example, which are sometimes called “kindergarten readiness” standards. Like Scott, I think this is the wrong term to use, because children will always arrive for kindergarten with very different skill sets and experiences.

And I think the COVID-19 pandemic is only going to exacerbate these differences. In Fall 2021, the variability in children’s skills will be greater than at any time in the past, given the recent disruptions. Rather than asking, Are the children ready for kindergarten?, we should be asking, Is kindergarten ready for the children? I’d argue that this is the question we should have been asking all along, because the onus is not on the children but rather on the programs, which need to be ready to assess the needs of the children who arrive each year so they can meet them where they are.

The role of assessment

Q: Does this mean that assessment will play a larger role during the 2021–2022 school year? Should programs assess children as soon as they arrive?

Heidi Lund: In some ways, Fall 2021 might feel like a repeat of Fall 2020, when there was a hesitancy to assess children—because some educators felt this was “stealing” instructional time, or because it required special logistics due to remote learning, or because we weren’t going to like the results anyway, so some schools and districts preferred to wait. But this year, it will be more important than ever to do fall screening. This applies to both preschool and kindergarten programs, to help teachers have a clear understanding of where students are and how their learning has been affected by the COVID-19 disruptions.

Yes, in some cases, the scores will be lower than what teachers and administrators are expecting. In other cases, the scores may be higher. In either case, the assessment will help educators to better understand each child in the program, so they can provide the “just-right” experiences for that child to thrive.

Alisha Wackerle-Hollman: In early childhood education, we talk a lot about differentiated instruction and how to build classroom environments that attend to children’s specific needs. Assessment sometimes gets a bad rap, but a well-designed assessment is a valuable tool for helping teachers to identify these needs, so they can allocate time and resources appropriately.

I agree that it will be critical to begin with fall screening, so we understand what children bring to the classroom. The caveat is that the assessment must be instructionally relevant, showing you where the needs are most critical so you can focus your efforts there. How you interpret your fall screening data should inform how the rest of the year will look—how you’ll allocate resources, which children you’ll identify for individual goals and progress monitoring, and when you’ll screen the children again. Without these data, you’re left to make assumptions about what children need, and you can’t differentiate in ways that lead to the best outcomes for them.

We designed the myIGDIs for Preschool assessment based on this philosophy. We recognize that teachers need to understand the baseline skills children have in key domains in a way that’s quick, easy, and instructionally relevant.

Formal assessment age

Q: What about claim that preschool children are too young for formal assessment?

Jan Bryan: Assessment is something that humans do all the time—especially young children. They’re constantly observing and comparing things: “How many trucks do I have?” “How many bubbles came out of the bubble machine this time?” “How many minutes until we get there?” Etc. They’re natural data-collectors, so assessment isn’t something that has to be forced on them.

Alisha’s point about instructionally relevant assessment is key here—once teachers have the data, what will they do with it? I really dislike the phrase “data-driven decisions.” Data don’t decide; humans decide. Screening provides valuable data for making decisions, but it’s not the only consideration. As an educator, I’m going to use all of the data available—both from formal assessment and from talking with and observing a child—to make decisions about what to do next. I’ll then continue to reassess based on what I’m seeing.

Scott McConnell: I always return to two points when thinking about preschool assessment. First, the assessment has to be developmentally appropriate. We can’t expect preschoolers to fill in bubble sheets, for example. That’s why curriculum-based measures like myIGDIs are brief, engaging, and are completed by the teacher and child working together. We actually want the assessment to be fun, with the children asking, “Is it my turn yet?”

Second, the assessment has to drive differentiated services for the students.We’re not trying to answer global questions, like “Are the children doing OK?” We’re trying to answer specific questions about what to do next: what does this child need, and this child, and this child? For this reason, preschool assessment needs to be very efficient, with a direct line between giving the assessment and then providing instruction.

Preschool advice

Q: What advice do you have for preschool educators as they plan for the 2021–2022 school year?

Alisha Wackerle-Hollman: I’m sure that teachers are already thinking about how to set up their classrooms to create spaces that really promote exploration and interaction. I think the home-to-school connection will also be a lot stronger in the new school year. Because of the pandemic, a lot of families went through a sort of “trial by fire,” where they took on a teaching role during at-home learning. I think teachers will need to support and build on this expanded educational partnership between families and children.

Teachers will also want to involve families more—by, say, explaining children’s seasonal screening results to them, and helping to ensure that what happens at home supports children’s development in the key domains we’ve talked about.

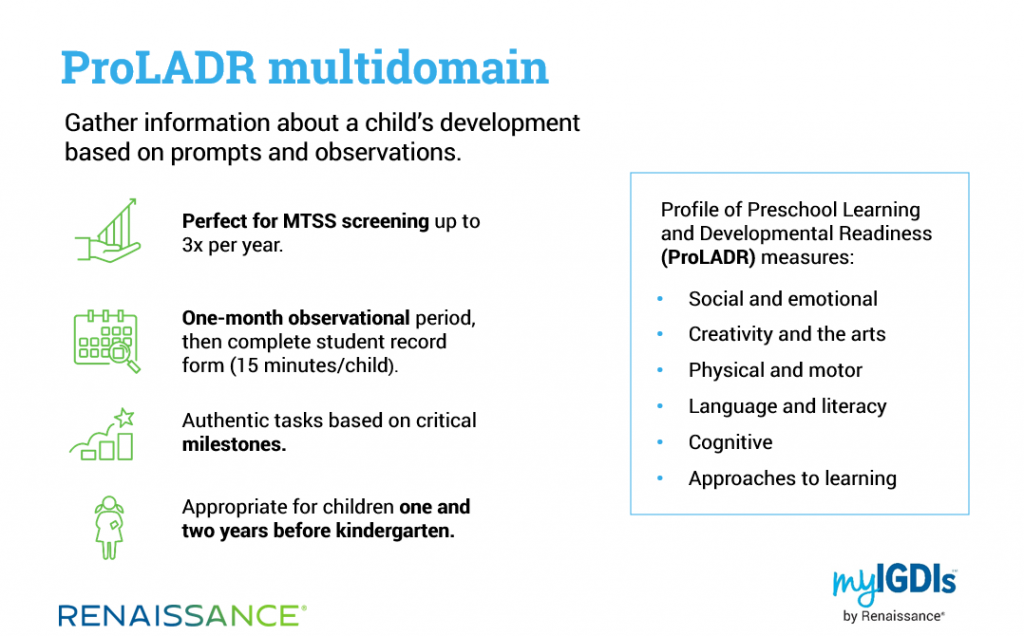

Heidi Lund: As the parent of a 3-year-old, I’ve definitely found myself wondering about the long-term effects of the disruptions. I had some valuable time with my son at home this year, but there were also times when, because of work commitments, I had to ask him to play quietly by himself for the afternoon. I think the ProLADR multidomain measures in myIGDIs—which assess social-emotional, physical and motor, cognitive development, and more—will be especially helpful for educators in the new year.

We talk a lot about children being resilient—and they are—but there will still be gaps that need to be addressed. The myIGDIs English and Spanish early literacy measures, along with the early numeracy measures, are important indicators’ of children’s academic development, but we can’t overlook the importance of taking a whole-child, multidomain approach.

Jan Bryan: That’s such an important point, Heidi. There are a lot of 3- and 4-year-olds who didn’t participate in preschool or daycare this year. Returning in the fall will involve a new environment for them, and they’ll probably have to relearn certain skills. Forming a line, for example, which can be stressful for young children. Or knowing how to take conversational turns, which is so important for later literacy development. I’d definitely reemphasize Alisha’s earlier point here—it won’t be a question of whether the children are ready for 3K, 4K, preschool, etc., but whether the programs are ready for the children.

Scott McConnell: I haven’t heard anyone say that benchmarks will be changing because of the pandemic, but we know it will be harder for a lot of children to reach those benchmarks. This means that in some instances, we’ll need to help students make up for lost opportunities quickly. In other instances, we’ll have to extend our supports and supplemental services for a long time. We also know that we’re going to have a greater mix of children than in the past—not just variations in skills, but greater variation in the age of the children enrolled in the same preschool and pre-K programs.

This means we’re going to have to be a lot smarter about providing differentiated services. Not everyone will need everything. Some children received a lot of attention and support over the last 18 months. Others clearly missed out on important opportunities. Teachers and program leaders will need to be even smarter—and this is hard—about identifying what each child needs, and then providing the services and support to meet these needs.

In some sense, preschool in 2021–2022 will look different than in prior years. We’ll have to focus even more closely on the skills and experiences that are most critical for future success. Without question, preschool needs to be fun and engaging—this is the natural state for preschoolers. Perhaps more than ever, though, “fun and engaging” will need to be connected to “learning and development.” Yes, we’ll still go on neighborhood walks and field trips, but how can we use these activities to expand children’s vocabulary and language skills? We’ll still have music and finger plays, but how can we more often sing about letters and numbers? Preschool teachers are incredibly creative and energetic, and the new school year will provide a great opportunity to direct those talents to make the best use of the time we have with our earliest learners.

Learn more

Looking for a developmentally appropriate assessment for your preschool or pre-K program? Explore myIGDIs early literacy, early numeracy, and multidomain measures. Also, please contact us with any questions or to request a personalized demo.